Kikuyu Roots and Origin

The history and origin of the Kikuyu have been mythologized; therefore, there exists various accounts.

The history and origin of the Kikuyu have been mythologized; therefore, there exists various accounts. This variation is as a result of the oral tradition through which the Kikuyu have passed their history down the generations and, thus are likely to have suffered several distortions. Consequently, it is challenging to separate fact from fiction since a lot of the stories have not been corroborated by research or any archaeology. However, some stories like the story of Gikuyu and Mumbi are always narrated by all the Kikuyu communities and clans. Even the Agikuyu migration stories are different with some arguing that they migrated from the Congo and Cameroon basin while others argue that they originated from a place called "Baci" in Ethiopia. The article herein tries to derive the origin and culture of the Kikuyu from the available evidence and existing stories.

The Gikuyu and Mumbi Story

The most famous story on the origin and roots of the Agikuyu is the Gikuyu and Mumbi story. All Kikuyu communities know this story and most of the people believe it is true and absolutely unquestionable. The myth of origin among the Agikuyu is similar to the Garden of Eden story where God (Ngai, Murungu, or Mwene Nyaga) is the creator, Gikuyu is the man and Mumbi (creator) is the woman. The story begins at the top of Kiri Nyaga (Mt. Kenya today) where God, who was walking with Gikuyu, showed him the land below (Mukurwe wa Nyagathanga) and instructed him to go to a location where there were many fig trees (Mikuyu). When Gikuyu descended and went to the location, he found a woman (Mumbi) who later became his wife. Ngai also told Gikuyu that he could communicate with him by praying facing the Kiri Nyaga (Mt. Kenya) or through offering a goat sacrifice under the famous Mukuyu and Mugumo trees.

Gikuyu and Mumbi went on to have ten daughters and no sons. When the daughters reached the age of marriage, they naturally wanted to have their husbands and families. As such, Gikuyu went to Ngai and told him that his daughters needed to get married. God told him to make a lamb sacrifice under a Mugumo tree and let the meat burn as a sacrifice to him. God or Ngai also instructed him to take his wife and daughters back home and then come back alone under the Mugumo tree. There, he would find nine handsome men who were happy to marry his daughters, and the Agikuyu would multiply and fill the land. The last-born daughter was too young to get married and therefore remained unmarried and according to oral tradition, she went on to become a single mother. Some oral traditions (hilariously) claim that the “curse” of single motherhood among the Agikuyu began from the fact that the tenth daughter never got married officially.

The land which was originally given to Gikuyu by God or the Garden of Eden of the Agikuyu in a place known as Mukurwe wa Nyagathanga or the tree where the Nyagathanga bird built its nest and lived. It is believed that this land is in Central Kenya near a village known as Gaturi in Muranga County. Indeed, the Gikuyu creation myth is deeply entrenched among the Agikuyu and most of them take it literally and consider it to be the absolute truth. Even after the emergence of new technologies such as gene mapping, the myth continues to hold huge sway among the Agikuyu people.

The Kikuyu Migration Story

Much controversy prevails over the migration story of the Kikuyu people, and as such, there are many theories on their origin. The one taught in schools today places the Agikuyu migration from Central African regions like Cameroon during the great Bantu migration ranging from 1200-1500 AD. Much attention, in this description, is focused on the Bantu people as an entity rather than the Kikuyu themselves. This narrative shows that the Bantu people migrated from their homeland in West-Central Africa, and then intermarried with the local Pygmies. Along the way of their migration, the Bantus were able to bring technologies and skills such as ironworking and cultivation of high-yield crops. The Bantus came to dominate and migrate throughout Central and Southern Africa over time. Scientists agree that there was Bantu migration; however, there is controversy regarding the time, routes, and motives. The Bantus were agriculturalists – farming dry rice, sorghum, millet, and beans. Although they did the planting on a subsistence level, they produced enough crops to meet their needs.

According to historians, the Bantu migration from the Western Central Africa region may have been caused by several factors such as overpopulation, famine, warfare, drought as well as the competition for natural resources including agricultural and grazing lands. The Bantu people went ahead to establish coastal settlements in East Africa which transformed into the Swahili Coast after the interaction with Muslim traders. Other historians believe that the Bantu migration happened in waves. The first wave was Southern West Africa, presently West Bantu, and East Africa, presently Great Rift Valley, the group that migrated south in the 1st millennium BCE. A third wave is thought to have occurred in the first half of the 1st millennium BCE, whereby the Bantus migrated into present-day Zimbabwe, Botswana, eastern South Africa, and Mozambique.

The Northern-origin Migration Story

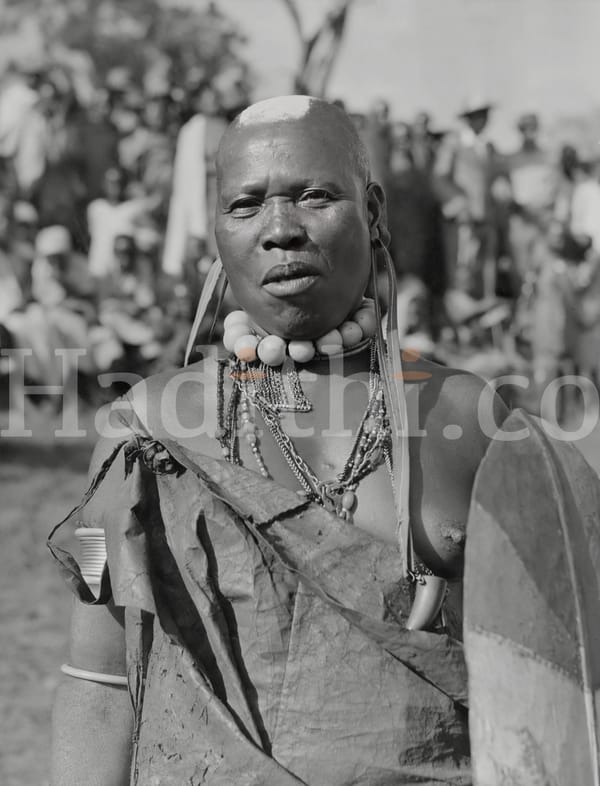

The land which is currently populated by the Agikuyu was initially a large primeval forest that as sparsely populated by the Gumba, Athi and Dorobo hunting and gathering groups. The recollection of the Gumba was that they were dwarfs who resembled the pygmies and lived in dug-out caves as well as tunnels. They also practiced beekeeping and iron working and in fact, it is claimed that the Gumba taught the Kikuyu how to work and smelt iron. The land was attractive due to the fertile soil, adequate rainfall, and cool temperatures especially when compared to its neighboring eastern border. The Agikuyu moved from the north, the place of present-day Ethiopia, into some place called Baci. They, in turn, extended further and consolidated their presence in Central Kenya by assimilating the people who were originally inhabitants, like the Dorobo, through marriage, and in return, with whom they exchanged food, livestock, and land for assimilation. Resisting assimilation, the Dorobo people moved south of present-day Tanzania. Little or no information has been known to exist about the history of Gumba; in fact, their history remains mysterious.

While historians generally agree that the Kikuyu mainly migrated and expanded through assimilation, there cannot be a total exclusion of occasional conflicts with the original inhabitants. The Gumba may have dispersed and migrated due to conflicts or population growth which led to increased forest clearance and diminished hunting grounds. Despite all these tensions, the two communities must have resolved to coexist peacefully because they needed each other; the Kikuyu needed hides and skins for leather from the Gumba, and members of the Gumba needed to acquire agricultural produce from their Kikuyu neighbors.

The Kikuyu share historical roots with other communities in Kenya such as the Mbeere, Tharaka, Meru as well as the Kamba who all come from a population referred to as the Thagicu who also migrated from the North. The Thagicu came from the North of today’s Ethiopia and settled around the Mount Kenya region between the 12th and the 14th centuries. As time progressed, splinter groups emerged and one of these groups migrated and settled in the southwest of Kiri Nyaga (Mount Kenya). The Kikuyu also trace their origins to a splinter group that occupied the region where the Tana (Thagana) and Thika rivers converge. From the Ithanga settlement, some subgroups migrated in a variety of directions including the north Nyeri, the northeast to Kirinyaga, and South to Murang’a over the following two hundred years. Others migrated further south in the Kiambu direction where they found a hunting population whom they referred to as the Aathi (Athi). They would go on to intermarry with the Aathi people and exchanged goats for land with them.

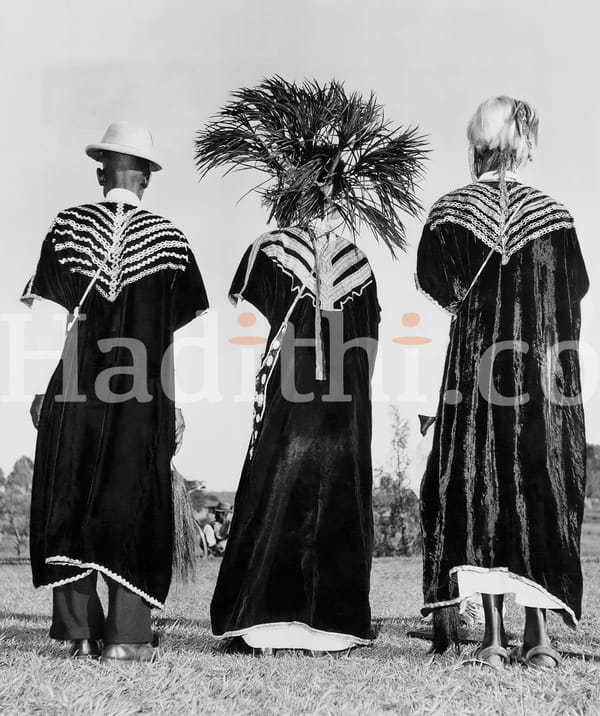

As the different Kikuyu groups went on to settle in different regions, a clan structure was created and each clan traces its origin back to a female ancestor who was a daughter of Gikuyu according to the Kikuyu myth of creation or origin. These clans as Acera, Agaciku, Anjiru, Ambura, Ambui, Angari, Aithiegeni, Aithirandu, Amuyu and Airimu. The tenth daughter (Wamuyu) completed what is known as kenda muiyuru. The name kenda muiyuru means ten and was used because it was taboo to count one’s children in the Kikuyu culture. To date, most of the Kikuyu women are still named after the daughters of Gikuyu and Mumbi.

Conclusion

The Kikuyu people's history and migration are complex and multi-dimensional, marked in equal measure by assimilation, resistance, and cooperation with other groups. On the one hand, oral traditions and myths offer rich materials for narratives, but on the other hand, they complicate establishing fact from fiction. Their expansion into Central Kenya involved peaceful integrations with indigenous populations—like Dorobo and Gumba—at times riddled with pockets of conflicts. Naturally, the interdependence dominating these communities brings sharper lines to bear on the dynamic and adaptive nature of the Kikuyu's cultural and historical development. It is this intricate past that explains a finer sense around tenacious legacy from the Kikuyu concerning their place in the general history concerning Bantu migrations in Africa.

References

Cagnolo, C. (1952). Kikuyu tales. African Studies, 11(1), 1-15.

Clark, C. M. (1989). Louis Leakey as Ethnographer: On the Southern Kikuyu before 1903. Canadian Journal of African Studies, 23(3), 380-398.

Lonsdale, J. (2002). Contests of time: Kikuyu historiography, old and new. In A Place in the World (pp. 201-254). Brill.

Middleton, J., & Kershaw, G. (2017). The Kikuyu and Kamba of Kenya: East Central Africa Part V. Routledge.

Muriuki, Godfrey (1974). A history of the Kikuyu 1500-1900. Nairobi, Oxford University Press.

Muriuki, G. (1978). The Kikuyu in the pre-colonial period.

Toulson, T. (1976). Europeans and the Kikuyu to 1910: a study of resistance, collaboration and conquest (Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia).

Were, Gideon S., and Derek A. Wilson (1985). East Africa through a thousand years: a history of the years AD 1000 to the present day. London: Evans Brothers.