Kenyan Life Before Independence: Insights from Mzee Kimani Njenga

Ever wondered how life was for Kenyans before independence? Well, today Hadithi shares insights from Mzee Kimani Njenga from Kiambu County who paints this vivid picture of life before independence both work and education in Kenya...

In a compelling interview with Mzee Kimani Njenga, a resident of Kiambu County born in 1941, we gain valuable insights into the work life and educational landscape of Africans in Kenya before independence. His experiences and recollections paint a vivid picture of the economic, social, and political challenges faced by Kenyans during this tumultuous period.

Early Life in Cura Town

Mzee Njenga was born in Cura Town, a small town in Kiambu County. The name "Cura" is derived from a man named Ole Shura, a Maasai whose descendants still reside in the Ngong area. Mzee Njenga's great-grandfather, Mr. Mashara, purchased land from Ole Shura, facilitated by Mr. Hinga, a sociable figure known for his connections with both the Kikuyu and Maasai communities. This background highlights the interconnectedness of cultures in the region during that time.

The Economic Landscape

Hardships Under Colonial Rule

Before independence, the economic life of Africans was characterized by significant hardship and exploitation. Mzee Njenga recalls how the arrival of white settlers drastically altered the landscape of work in Kenya. The first Europeans to arrive were missionaries, such as Ludwig Krapf, who came to Kenya in 1884. Their arrival was soon followed by settlers seeking fertile land for agriculture.

Settler Occupation

Kiambu County, known for its rich soil, became a prime target for white settlers. Mzee Njenga recounts how many areas, including modern-day Redhill, Kitisuru, Alliance High School, Kikuyu, and Fort Smith, were once owned by Africans but were appropriated by the settlers. This land dispossession fueled anger and resentment among the local population, as many families lost their ancestral lands and livelihoods.

Exploitative Labor Practices

The economic conditions for Africans working on settler farms were dire. Mzee Njenga shares that his late father earned a mere 1 Kenyan Shilling per day working on a coffee farm owned by a white settler. This meager wage amounted to only 30 Kenyan Shillings per month, leaving families to struggle for necessities. Moreover, compensation for labor was often inadequate and humiliating. Workers like Mzee Njenga’s father would receive a can of maize flour every Saturday as part of their wages, highlighting the exploitation faced by African laborers. The combination of low pay and harsh working conditions created a bitter environment, leading to growing discontent among the African population.

Education Life in Kenya

The Education System

Mzee Njenga began his education at Cura Primary School in 1951. During this time, schools in Kenya were scarce and often scattered across the country. The education system was structured in levels, starting with a common entrance examination. Success at this level allowed students to join intermediate schools, but enrollment was highly competitive, with many students repeating the entrance exam multiple times—some for as long as five years—before being accepted.

Independent Schools

After his initial schooling, Mzee Njenga enrolled in Kahuho School, one of the few independent schools established by Africans. Another notable independent school was Githunguri, now known as Saint Joseph School. Dagorreti High School, referred to as "Waithaka" at that time, was also part of this movement. These independent schools were constructed by Africans for several reasons:

● Empowerment: The primary goal was to educate the local population about the importance of independence and self-governance.

● Control: By establishing their schools, Africans sought to take control of the educational narrative and ensure that their children received an education that aligned with their cultural values and aspirations.

Among the prominent figures associated with these educational institutions was Mbiu Koinange, who founded the Githunguri School. The school became a beacon of hope and learning in the community. Notably, Margaret Kenyatta, the wife of former President Uhuru Muigai Kenyatta, also attended this school as a teacher, showcasing its significance in the educational landscape of the time. While some schools like Cura were initially government-funded, they soon became platforms for African education and empowerment.

Social Dynamics

Community Resilience

Despite the oppressive conditions, Mzee Njenga reflects on the resilience of African communities. Social bonds were vital during this period, as families and neighbors supported one another in times of hardship. The communal spirit fostered a sense of solidarity that was crucial for survival.

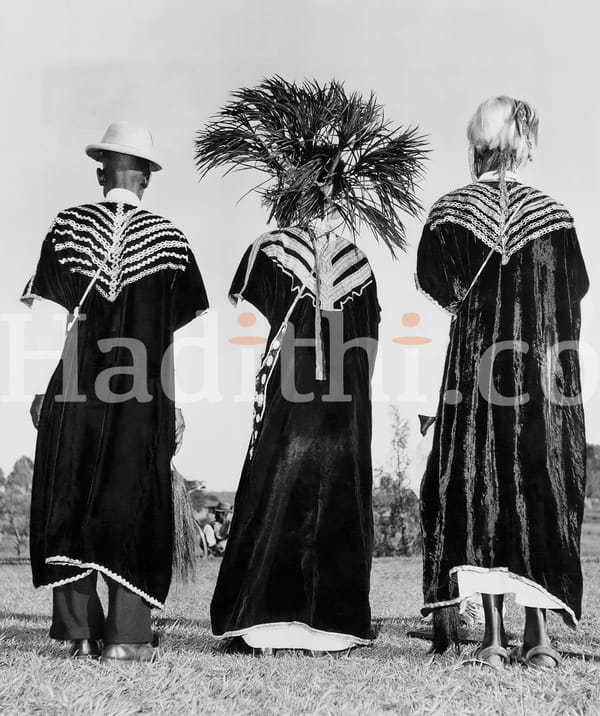

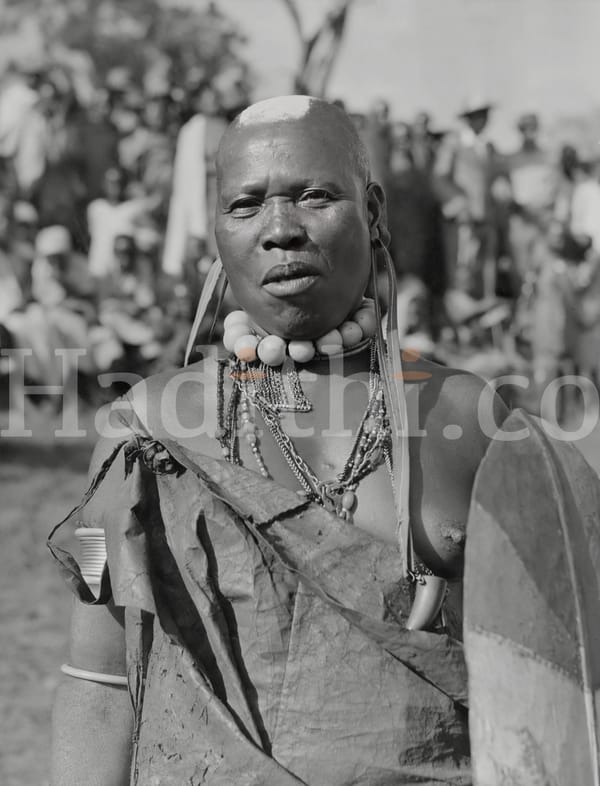

Cultural Heritage

Work-life was not solely defined by labor exploitation; it also encompassed cultural practices and traditions. Many Africans maintained their customs, including farming techniques and communal rituals, which were passed down through generations. These cultural elements helped preserve a sense of identity amidst the colonial upheaval.

Political Awakening

Growing Discontent

The harsh realities of work life under colonial rule fostered a growing political discontent among Africans. Mzee Njenga recalls how the injustices faced by workers, combined with land loss, ignited a desire for change. This sentiment contributed to the broader push for independence.

Early Resistance

As awareness of their rights and injustices grew, Africans began to organize and resist colonial rule. Workers’ movements and political organizations started to emerge, laying the groundwork for the eventual struggle for independence. Mzee Njenga’s experiences reflect the early seeds of resistance that would blossom into a national movement.

Education as Empowerment

The pre-independence era was marked by significant social and political challenges, with education viewed as a crucial tool for empowerment. The establishment of independent schools provided education and fostered a sense of community and collective identity among Africans. Mzee Njenga's recollections paint a vivid picture of the striving spirit of the Kenyan people as they navigated the complexities of colonial rule.

Conclusion

Mzee Kimani Njenga’s insights into African work life and education before independence reveal a complex landscape of hardship, resilience, and eventual awakening. The economic exploitation faced by Africans, coupled with the loss of land and cultural identity, created fertile ground for discontent. Despite these challenges, communities found ways to support one another, preserving their heritage while pursuing education as a means of empowerment.

As Kenya continues to honor its journey toward independence, it is crucial to remember the sacrifices made by individuals like Mzee Njenga and the broader community. Their stories serve as powerful reminders of the strength and resilience of the Kenyan people in the face of adversity, laying the groundwork for future generations to engage in the struggle for independence and self-determination.